In our quest to complete a phylogeny for all living birds, extinct species play a big role as well. Fossils provide calibrations to date the tree. But, they also provide sometimes unexpected insight into how each group of birds evolved, including were they originated and how they changed over time. As our team has advanced our understanding of extant passerine (perching bird) phylogeny, we have also been delving into the surprising past of this hyper-diverse group. Modern passerines include many familiar backyard birds such as sparrows, chickadees, and crows – and with over 6000 extant species represent more than half of present day bird diversity.

Open Wings paleontologist Daniel Ksepka, working with colleagues Lance Grande of the Field Museum and Gerald Mayr of the Senckenberg Research Institute, recently identified two new extinct bird species that were the first to evolve finch-like beaks. Fossils of the new species, named Eofringillirostrum boudreauxi and Eofringillirostrum parvulum, were discovered in Wyoming and Germany. The exquisite fossils date to 50 million years ago, a time when both regions were covered by subtropical forests.

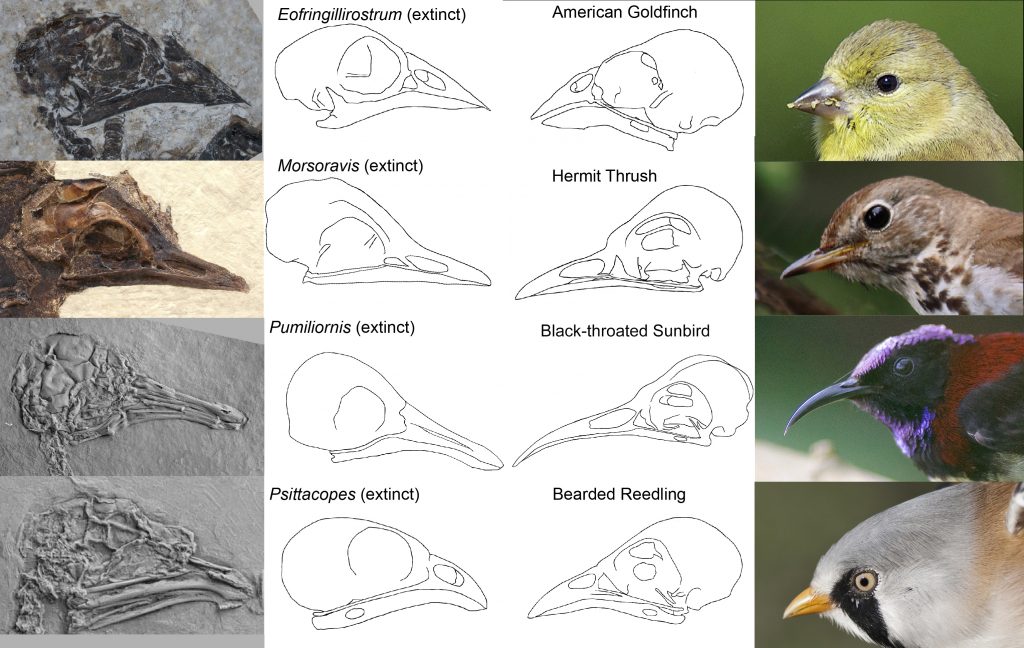

Despite their dominance of many modern ecosystems, passerines have a very sparse fossil record. The two Eofringillirostrum species appear to have been part of an early passerine family called Psittacopedidae. The finch-like beak of Eofringillirostrum is remarkable because it reveals that members of the Psittacopedidae evolved all types of feeding specializations in the distant past, only to go extinct and be replaced by modern species. Whereas the finch-beaked Eofringillirostrum evolved to feed on small seeds, it had close relatives with very different specializations including the slender-billed Pumiliornis tessellatus which drank nectar, the long-billed Morsoravis sedilis which likely fed on fruits and invertebrates and the odd, short-beaked Psittacopes lepidus which may have had a mixed diet. All species of the Psittacopedidae seem to have gone extinct by 30 million years ago. Modern perching birds like finches, sunbirds, and thrushes took over the same ecological roles. In a way, modern perching birds re-invented the wheel – or more accurately, re-invented the beak.

The early success of Eofringillirostrum and its relatives raises the question of why they ultimately died out. One major difference between early perching birds and modern species is the foot structure. In Psittacopedidae, the fourth toe is reversed, suggesting they were limited to nesting in tree cavities. Modern perching birds have a dazzling variety of nesting strategies, which may have allowed them to outcompete more archaic species in new environments.

The study was featured on the cover of the February 18th issue of the journal Current Biology and is accessible here.